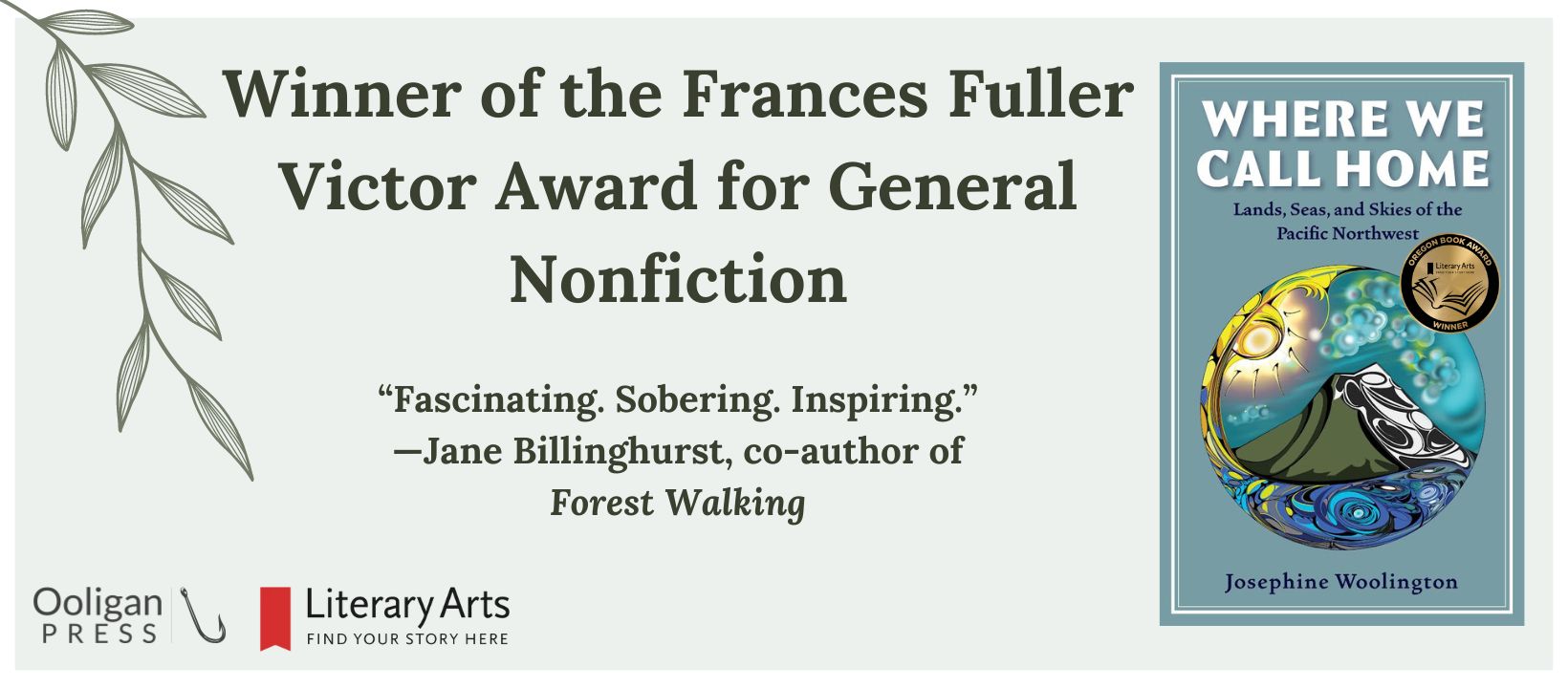

“Where We Call Home: Lands, Seas, and Skies of the Pacific Northwest” Winner of the Oregon Book Award

Josephine Woolington receives First Last Award for Nonfiction from Literary Arts Ooligan Press and Josephine Woolington’s collection of essays titled “Where We Call Home: Lands, Seas, and Skies of the […]