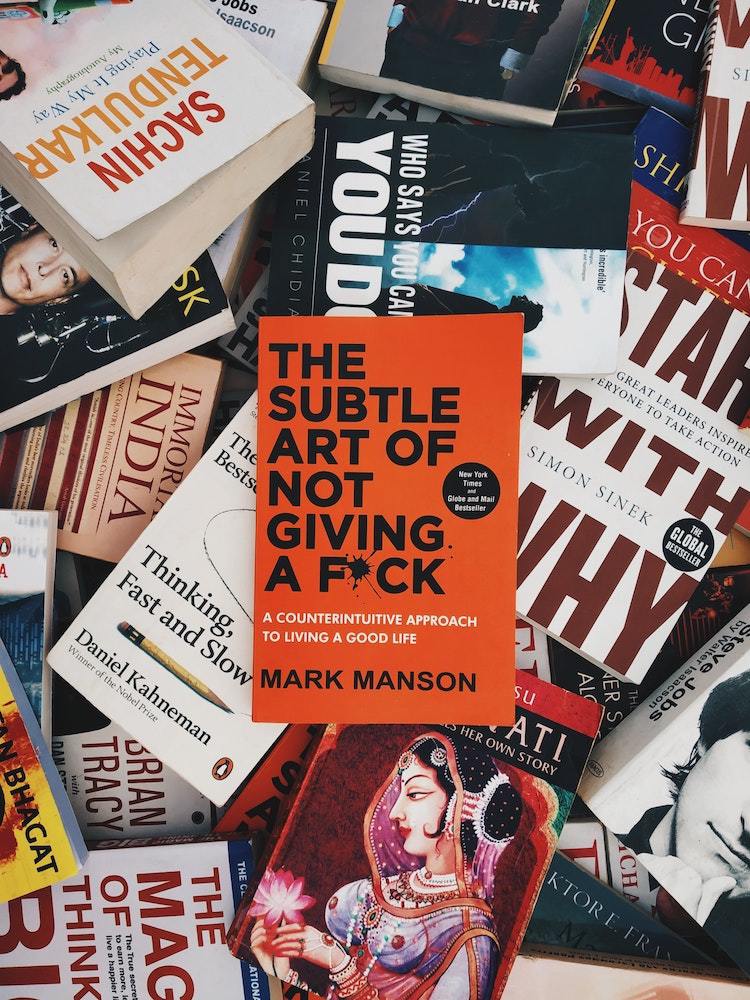

I Didn’t Like This Book Cover…So I Made My Own

It’s not a bad cover by any means, but in a world where the books we read often perform as style accessories on top of mere storytelling vessels, I knew there was an opportunity to give her something more unique—something she’d love to pick up based on the cover alone. Not to mention that personalized gifts are always the best anyway!