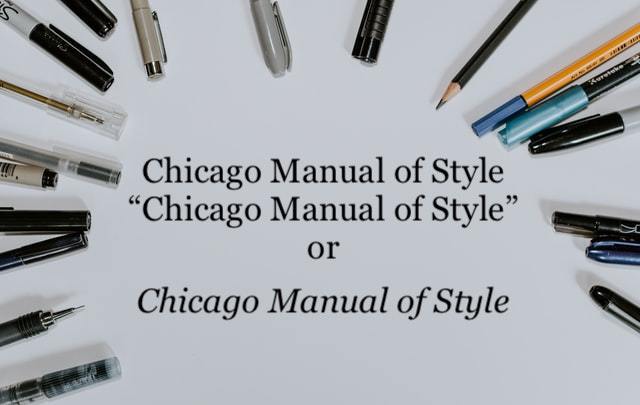

Manager Monday: The Role of Copy Chief

Ooligan Press is a student-run trade press that operates in conjunction with the book publishing master’s program at Portland State University. Those of us inclined to bite off a bit more work operate as project managers (those who manage the publication of a book project) and department managers (those who run the various departments within the press). As copy chief it is my responsibility to oversee and edit all the copy that goes through the press.