For most of my life, I have thought of myself as a writer. So, I went to lots of writing groups and circles and workshops and classes and retreats, and I also read a fair amount of writing content on social media, especially Twitter (now X).

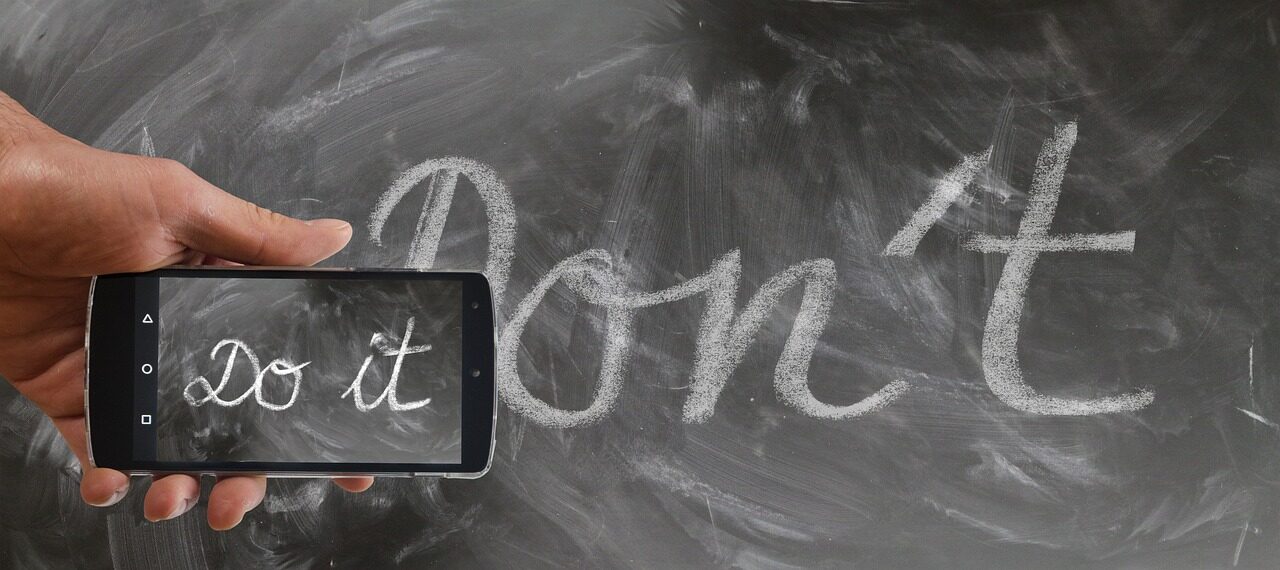

Now that I’m one year into the book publishing program at Ooligan, I can clearly see a disconnect between what writers talk about among each other and the publishing world. This is especially true when it comes to writing “rules” that circulate in writing circles and on all the writing-related hashtags.

One writing rule that circulates around the “writingverse” in online spaces with some frequency is that no one should write their book in the present tense. I’ve seen and participated in heated debates about whether present tense is ever allowed. (I say it is, and in general try to steer myself and others away from any absolutes, and anything involving “always” or “never.”) Some people in publishing do have their preferences, and sometimes those are strong. But there is no hard-and-fast rule.

I read a lot in the mystery and thriller genre, and no matter how many rounds of “no present tense” go around on Twitter, I notice that more and more mysteries and thrillers coming out in recent years are written in present tense. A clear example that the strict rules that circulate through the world of writers don’t hold for what publishers are acquiring and publishing.

Some other examples I’ve seen in recent years include missives that authors should never use semicolons, never use em dashes, and never give your book a prologue. Many of these “rules” come from individual people’s own reading preferences and pet peeves, and perhaps from seeing examples of specific things done poorly or ungrammatically. But they aren’t universal truths like they are often framed and passed on.

Another writing rule that makes the rounds every short while is “no head jumping.” Head jumping refers to when a story is told through one character’s eyes, often in a third-person limited POV, and then suddenly it’s told through another character’s perspective.

This one, to my eye at least now that I’m on the publishing side, is in a different category than some of the others, because it’s less about personal reading preferences and peeves and more about something that could cause confusion for the reader.

It used to be that when a writer wanted to change perspectives, they’d start a new chapter. That way, each chapter is in only one head, and the character’s name is written at the beginning of the chapter, making it clear and easy for the reader to tell whose head they’re in at any given part of the story. There are still plenty of books that do exactly that. The most recent book I finished, The Book of Cold Cases by Simone St. James, employs that technique. I’m also seeing a trend in which there might not be a full chapter break between different characters’ headspaces, but a simple section break often delineated by one or two lines of white space to indicate a shift.

Louise Penny, bestselling author of the Chief Inspector Armand Gamache series set in Quebec, takes head jumping a step further. She doesn’t even include white space to indicate a jump. She uses section breaks, but they indicate time or space changes. Within any one section, the perspective—or head—is fluid. Sometimes there are multiple, shifting heads in just one section. Lots of writing circles I’ve been in would have proclaimed all of this an absolute deal-breaker no-go in the writing world. But it certainly hasn’t held Penny back, as she just released the nineteenth book in the series this past October and it was an immediate bestseller.

It probably wouldn’t work for every author, but then again, what would?

One year into this publishing program, my advice to authors would be to shift away from this sort of specific instructions, and focus more on reading widely in the genre they want to publish in. And not just the greats or the faves or the classics that defined the genre, but as much as possible in different levels and subgenres. I would implore authors to read what’s currently being published, voraciously. That’ll not only demonstrate that there are no blanket rules against em dashes or semicolons or present tense or even head jumping, but also expose authors to current practices and fashions.