Ooligan Press hosted the Transmit Culture: The Future of Children’s Reading panel last October, which focused on how ebooks were shaping children’s education. One thing that interested me was hearing that teachers were specifically looking for digital books designed for multimodal learning—learning that engages different sensory modalities like sight and sound to fit different learning styles. It seems like a perfect way to make interactive learning engaging.

I studied philosophy in my undergraduate years, and my school’s philosophy program had a big focus on the philosophy of perception. I studied Molyneux’s Problem, which asked if different sensory modalities communicated the same information by asking if someone who had touched a cube and a sphere but never had the faculty of vision would recognize the shapes if they were suddenly granted sight. If the corners and curves are understood right away, the senses themselves hold information about what corners and curves are. If the person doesn’t understand right away, it’s experience with a sense that teaches what a corner or a shape is in relation to the sensory modality.

Problems like this made me pay special attention when I came across the idea of enactivism. Enactivism, as Alva Noe explains at the beginning of Action in Perception, holds that “perception is not something that happens to us, or in us. It is something we do.” Instead of treating perception as something to be analyzed in snapshots, as often happens in the philosophy of perception, enactivism holds that perception is to be understood over time, with an active perceiver manipulating what they’re perceiving. Ask someone to close their eyes and place a ring in their hand, and they’ll move the object in their hand to get a sense of its shape. Forbid them from moving their hand, and they’ll have a very difficult time figuring out the shape from touch alone. The more opportunities Molyneux’s newly-sighted person has to manipulate the cube and sphere, perhaps by moving their head or body to see the shapes from different angles, the more opportunities they’ll have to understand what they’re perceiving and relate it to what they know of these shapes from touch.

Though it’s treated as a theory of perception, it offers insights into how learning may work. The perceiver’s ability to manipulate what they’re trying to perceive lets them understand what it is. This is surely what is meant when people say they learn best by doing. And learning what a real object is involves learning the agreement between the different sensory modalities—one can see there is a relationship between the feeling of a ball, the sight of it, and the sound it makes when bouncing off different kinds of surfaces.

What’s interesting about digital platforms, and what makes them challenging, is that the agreement between the senses has to be created by a programmer. A programmer can make tapping on an object create a sound, leave it silent, have it create a delayed sound, or create any other reaction they want. Because these connections are authored and because they’re not inherent to the type of object being depicted, what one learns about these interactions may only be true in one case. What we learn about a baseball is going to have relations to all baseballs, but what we learn about an app may only be true for that one app. Added to the problem is that there’s no connection between touch and what is being represented. The tactile sensation of interacting with any two apps on an iPad is identical.

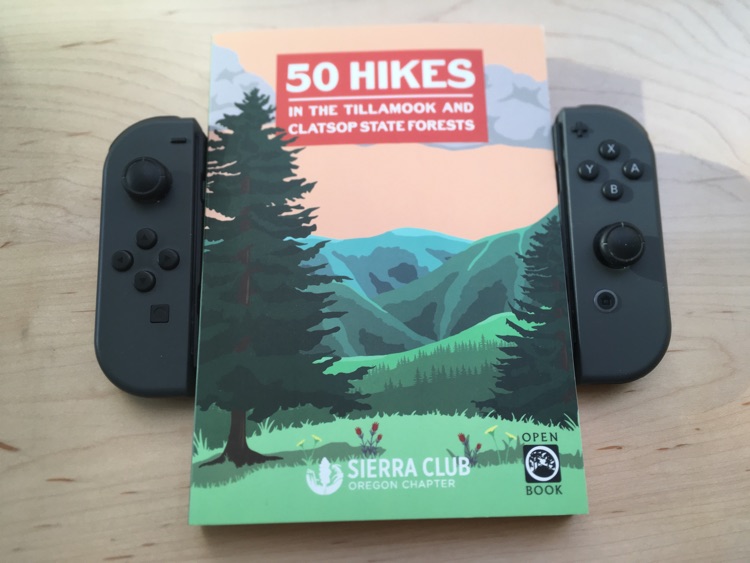

I’m a big believer in digital reading, but the benefits of digital reading for young learners are difficult to realize, especially without a lot of thought about how sensory modalities relate to each other and without a strong emphasis on how young learners can manipulate what’s represented on the screen. One novel approach is suggested by Nintendo’s new Labo line of toys. Nintendo has designed papercraft accessories for their Switch gaming console, which users have to physically assemble to play with. Nintendo has found a way to extend the functionality of the tablet-like Switch using a form of print, adding tactile manipulation to give a new dimension to play. It’s worth investigating whether this enactive union of electronics and print has any applicable lessons for publishers trying to bring enactive learning to digital publishing.