In my experience, there are two types of writers: those who persistently want to keep in the final manuscript every single idea that first occurred to them, and those who use what they know to be poor or sometimes altogether terrible ideas as mere placeholders until they come up with better ideas in the editing phase. Without the keen eyes and second opinions of developmental editors—and without the willingness of authors to read and reread their first drafts for storylines and characters that could and should be polished, fleshed out, or completely scrapped—some of the best-known classics of today would look very different, evoking in readers far more hilarity, horror, or quizzical curiosity than the final drafts that were actually published.

Not all great hits in the world of publishing and storytelling start off with a bang. In fact, many well-known authors had ideas upon ideas for their stories, characters, and voices that were scrapped before their final drafts were produced—final drafts that might be surprising in comparison to the original ideas from which they developed.

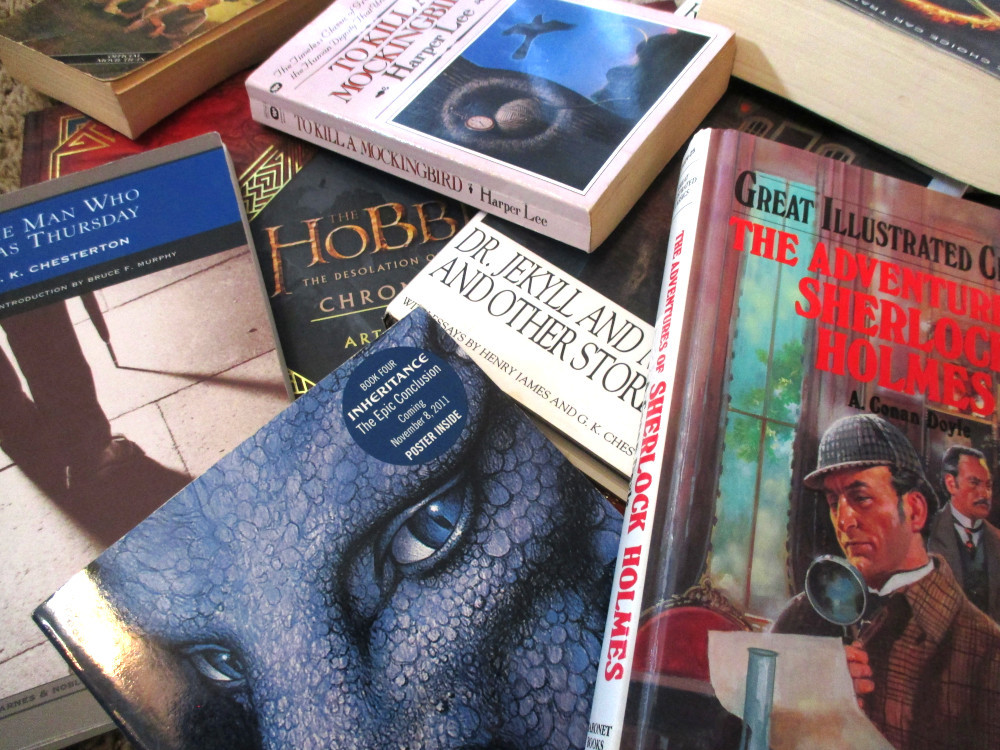

The recently published Go Set a Watchman by Harper Lee is a good example of a first draft that was scrapped in favor of a rewrite that became a classic. Lee’s first draft was discovered in 2014, decades after To Kill a Mockingbird was published, and was itself published a year later by HarperColllins. The manuscript is set twenty years after To Kill a Mockingbird, and it features a grown-up version of the main character, Scout (Jean Louise Finch), and an upending focus on the civil controversy of the time. Atticus, Scout’s father, is shown in a different light—one more thoughtful and grave—and Scout’s childhood is shown only in flashbacks. Go Set a Watchman could be read as a sequel to Lee’s iconic novel, but it was really meant to be a draft of the ideas she would convey in her final masterpiece.

In addition to thinking about plot, developmental editors must also pay attention to seemingly more minor things, like names. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle went through several name ideas before deciding on those with which he would christen his famous detective-and-doctor duo. “Sharrington Hope” became “Sharrinford Holmes,” a name still known by many a Holmes fan; but this didn’t stick once Doyle started sorting out the features of his character and decided he wanted a sharper moniker. He had already encountered the name “Sherlock” when reading about an inspector who was often written about in newspapers, and now the name “Sherlock Holmes” cannot fail to be recognized by any who encounter classic fiction. Dr. John Watson’s name also went through a process of metamorphosis, as Doyle originally intended to name him “Ormond Sacker.”

This is where the process of editing is vital. A first draft, though nostalgic, does not always have the trappings of a classic tale, just as not every character’s original name is the one he’ll be remembered by. Whether by the process of elimination or by brainstorming new ideas, every author should take a hard look at her manuscript and apply a ruthless pen to its pages. Hits do occur—some of them with very little help on the part of the developmental editor—but just because a writer is enamored with a first idea does not always mean it is a good one that will bring something worthwhile to readers’ bookshelves, as many a fantastic writer has learned the hard way.