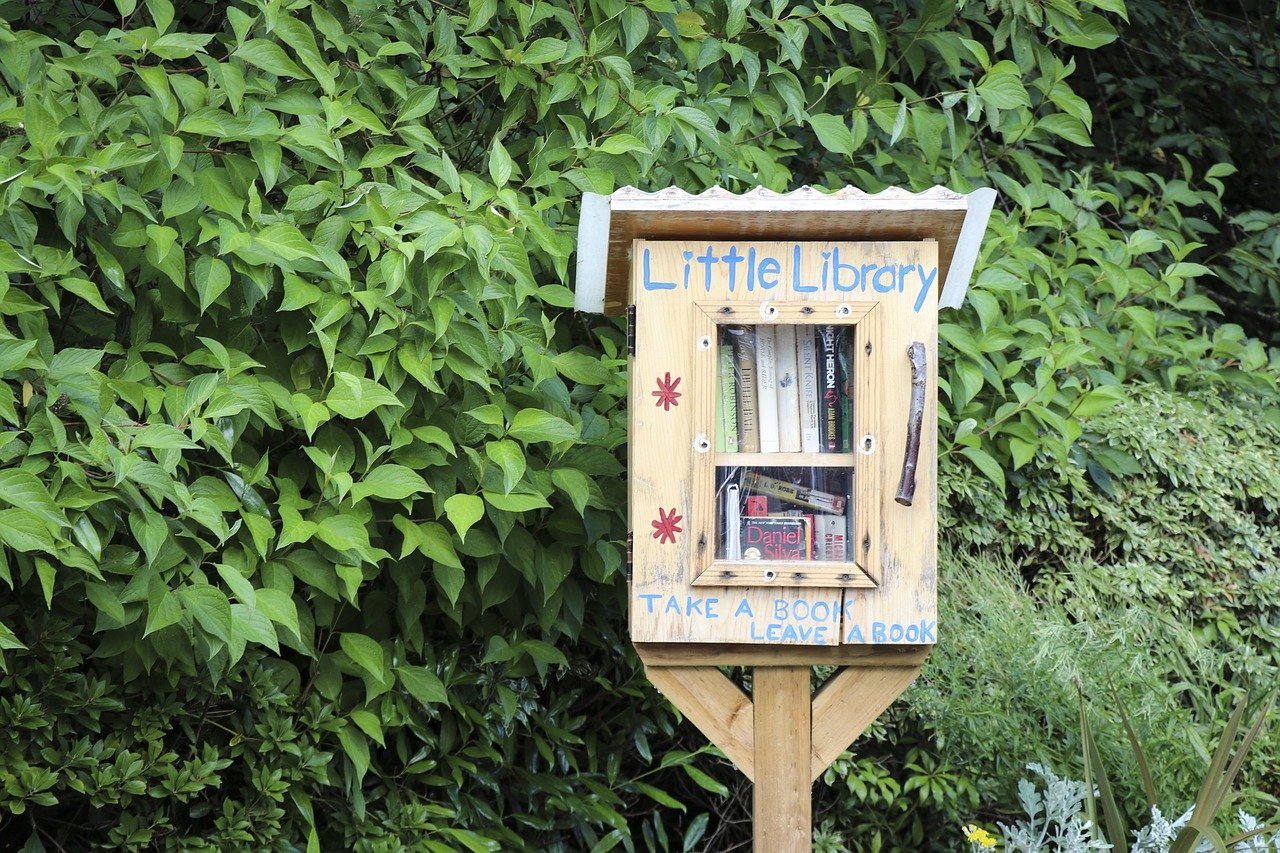

I recently came across a first edition reprint of Fowler’s Modern English Usage—a book I had been meaning to read—in my neighborhood Little Free Library. Like The Elements of Style by Strunk and White and The Chicago Manual of Style, this book is often recommended to people learning how to write and edit, but it’s one I hadn’t had the chance to read yet.

The copy I found is a 1952 reprint of the original 1926 edition. Though outdated, I thought this original version would be interesting given its historical significance while also being a fun read. As someone who can get lost for hours in a style guide (I doubt I am alone here considering how many Oolies I know who can get lost in NPD Bookscan or on Merriam-Webster), I was excited to come across this copy.

So, what exactly is a dictionary of usage, and how is it different from a style guide or standard dictionary? Generally, dictionaries are “descriptive,” while a style guide is “prescriptive.” A dictionary describes the way we currently use language, while a style guide prescribes specific rules or conventions for a particular group to follow to keep the work of the group (reporters, a company, editors, etc.) consistent and cohesive.

A usage dictionary falls somewhere between the two: it is both prescriptive and descriptive. It doesn’t have the definition of words like a dictionary but rather explains how to use words whose usage can be confusing or problematic, often offering historical context. According to Britannica, its purpose is to “record information about the choices that a speaker must make among rival forms.” If you’ve ever wondered whether you were using the right word, need to know more about its origin, or want to see other notable uses, a usage guide is a great resource.

So, I brought the book home. The print is tiny, and the book has a formal look—rather like a bible, which isn’t too surprising since it was written by an Oxford scholar nearly one hundred years ago. I opened it, expecting the book to be full of rigid lists and old-fashioned rules, but I was wrong.

For one thing, it is surprisingly funny. Henry Fowler was a well-educated person who didn’t quite take to his first two careers in teaching and writing. According to English Heritage, he and his younger brother decided to move to secluded, neighboring granite cottages on the island of Guernsey in the English Channel to study and write about language (and swim a lot). The book is full of his idiosyncrasies, extended opinions and observations (three dense pages on split infinitives), hilarious examples of the silly things writers come up with in order to follow the “rules,” and wit—yet lacks the self-righteous tone this type of writing can come with. As it turns out, Henry Fowler was an early champion of plain language.

I also borrowed a copy of the fourth edition for comparison, which is edited by a more recent Oxford lexicographer, Jeremy Butterfield. Changes include new entries and updates on word usage to reflect the way language has evolved, and thankfully, the addition of some much-needed white space.

Butterfield kept the general tone of the entries, as well as Fowler’s ample use of citations. But in the newer version, we now have the benefit of considering Ezra Pound’s efforts at sapphic prose and Alanis Morrissette’s questionable use of “ironic.”

The most recent edition also makes a reasonable case for not taking the word “literally” quite so literally while also explaining the original meaning of the word and its centuries-long, controversial history. It also dispelled the myth that nauseous can’t mean nauseated and that sometimes it makes more sense to end a sentence with a preposition. Surprisingly, Fowler has made me more flexible in my thinking about writing.

I will never memorize the endless rules and conventions, but having a good reference like this is invaluable, and I am so grateful that I came across it. Long live the Little Free Library!