A thoughtful developmental edit is essential to the success of every book. While a developmental edit presents many challenges, one of the largest is remembering a seemingly obvious point: it’s not your story, it’s the authors’. The purpose of a developmental edit is to help the author tell their story better, without taking the story away from them.

It is easy to be a critic. We do it effortlessly every time we read a book, see a movie, or watch a TV show: “That scene didn’t work.” “This dialogue is stilted.” “That character is shallow.”

Having a critical eye is essential to doing a good developmental edit; it’s our job to critically appraise the “bones” of a story—the structure, characters, pace, flow, and dialogue. “Mending the bones” is the entire purpose of developmental editing.

The trick is to turn your critical observations into useful suggestions and questions for the author. “Here are some ideas to make this scene work better.” “You might want to think about how to make this dialogue sound a bit more natural.” “Have you thought about this character’s motives and conflicts?” Thoughtful suggestions and questions help the author strengthen their story.

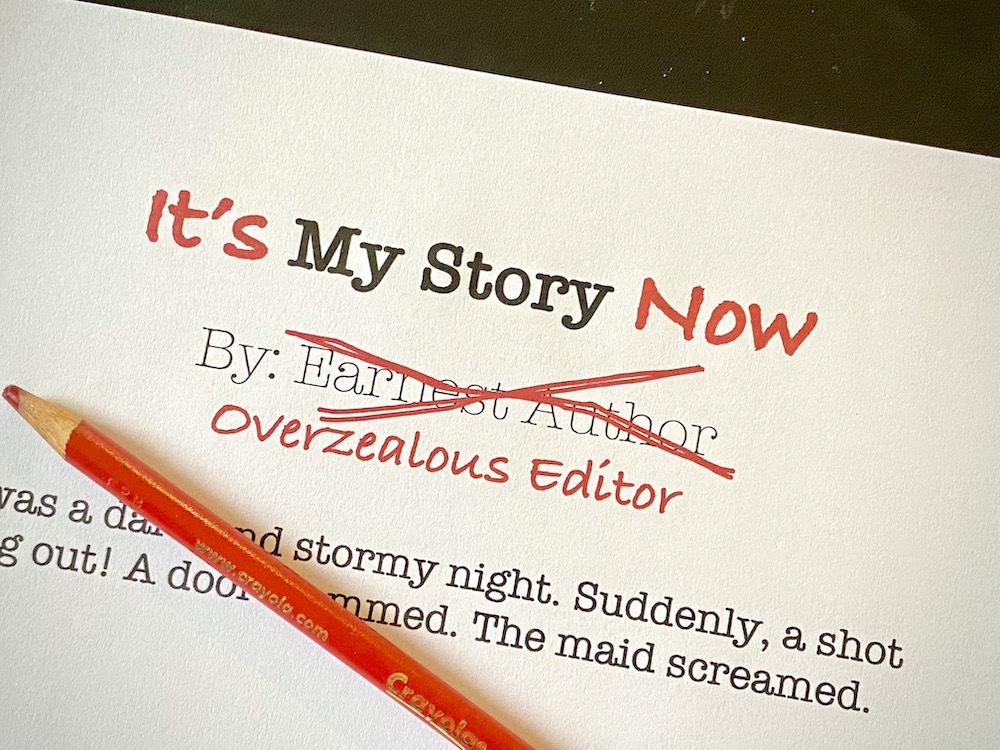

It is so easy to go beyond just asking questions and start making suggestions. The more deeply we get into a text and the more we think about its weaknesses, the easier it is to make sweeping judgments about the structure, characters, and plot. From there, it is a short step to fashioning our own solutions to the problems we have found. “If it were my book, I would have written it this way.” “I don’t like the protagonist at all; I would delete him altogether and create a different character.” If we package these solutions into a persuasive DE letter and the author makes all the changes we have suggested (or rather, demanded), then we have taken the book away from them and made it our own.

This can be a particularly easy trap to fall into if the story needs a lot of work. Rather than go through the sometimes tedious process of asking questions and making suggestions, we are tempted to just tell the author what to do to make the story better—or, at least, make it better to us. And that is the one thing we must not do.

The reality is that every manuscript needs help; this is why we have editors. Nonetheless, we make the story better, not by imposing our judgments, but by helping the author strengthen theirs. But before we can do that, we have to put ourselves in the right mindset. It’s the mindset of seeking to understand what the author is trying to do with their book.

Renowned editor Nancy Miller explains it perfectly: “It is empathy that is perhaps the quality most crucial to the editing process: the ability to help an author make the book the best book it can be…while keeping in mind that it is always the author’s book.”

In so many aspects of life, more empathy is the solution to the problem. Empathy is the key to good developmental editing and to publishing a book that both you and the author can be proud of.