Kali VanBaale’s debut novel, The Space Between, earned an American Book Award (the Independent Publisher’s silver medal for general fiction) and the Fred Bonnie Memorial First Novel Award. Her short stories and essays have appeared in Numéro Cinq, The Milo Review, Northwind Literary, Poets & Writers, The Writer, and the anthologies Voices of Alzheimer’s and A Cup of Comfort for Adoptive Families. She currently lives and writes on an acreage outside Des Moines with her husband, three children, and highly emotional dog.

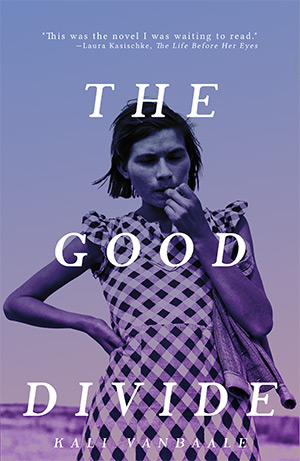

Her second novel, The Good Divide, is forthcoming from Midwestern Gothic Press in June 2016. An excerpt is included following the interview.

Like The Good Divide’s protagonist, Jean Krenshaw, you spent your young life on a dairy farm in the Midwest. The details of Jean’s daily domestic rituals are so richly realized, I’m not at all surprised you had firsthand experience! Can you tell us about the kinds of emotions you experienced while reflecting on your childhood setting writing this novel?

Looking back, I see that I was writing my odd version of a love letter to my childhood family farm in The Good Divide, and it was very emotional to spend time in that world again. When I started working on the book, my parents were still farming and running the dairy, so I had regular contact with the life and all its hardships and sacrifices, and the details were at the forefront of my mind. By the time I finished the book, though, my parents had retired and the farm was sold, so the story now has an element of sadness for me, a time and place gone by. So many of those old family farms, like the one I grew up on, are no more. Farming, and especially dairies, are moving to corporations. To capture a piece of that fading American life feels doubly important to me now.

Can you tell us about the very first inspirations for The Good Divide? When did you first begin working on the manuscript?

The first seed for this story started germinating years ago when my dad and his younger brother took over the dairy from my grandfather and lived in houses with their wives and children just a mile or so apart. The close quarters and working relationship with everyone in each other’s business sometimes created conflict and tension. But shortly after I started the book, I heard an old story about two central Iowa sisters at the turn of the century who’d had a falling out and built identical houses just yards away from each other so they could spy on each other from their second floor balconies. I don’t know if any part of that story is true, but I loved it so much that it ended up giving final shape to what would become The Good Divide.

Ben Tanzer reviewed your book saying, “this is what a page-turner feels like,” and I couldn’t agree more. I devoured The Good Divide in two sittings. The twenty-four chapters move readers between different seasons in Jean’s life throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and yet the unfolding drama feels direct and deliciously immediate. Can you tell us about your strategies for pacing the novel?

That’s a serious compliment. Thank you! I’ve worked on this book on and off for the last ten years, and the plot and structure have changed throughout the many different drafts. I rewrote and revised it at least a dozen times before I finally landed on the version you see today. For many years, I stubbornly had this third structure where I had the early ’60s storyline in Part I, the entire ’50s storyline in one chunk in Part II, and the last half of the ’60s storyline in Part III. But the content editor at MG Press, Michelle Webster-Hein, suggested I layer the two storylines together so that one didn’t disrupt or overpower the other, and then both would reach their narrative climax side-by-side near the end of the story. It was a huge amount of work to basically take the entire book apart and put it back together again, but Webster-Hein was totally right. The layered structure alleviated the previous uneven pacing problems that I’d battled for so long. Then my MG Press managing editors, Jeff Pfaller and Robert James Russell, helped me polish up those changes in the final version. I learned a lot about structure and pacing from this book and how they can work together—or against each other. Webster-Hein is also a VCFA grad, by the way, so OF COURSE she’s brilliant, and I trusted her advice.

What a supportive publishing experience! I really appreciate you demystifying some of the editorial journey. There is something about emotional turmoil set in the countryside of middle America that feels timeless, and yet, The Good Divide reads so relevantly for our current social and political moment. With your unflinching examination of family, lust, responsibility, and death, I see strong comparisons between The Good Divide and A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley. Was that an influence for you, and comparatively, what do you believe makes your novel so timely?

A Thousand Acres is such a brilliant book, isn’t it? It definitely influenced my writing and gave me encouragement that rural, midwestern, domestic family dramas have an audience. I hope what makes The Good Divide feel timeless is that at its heart, it’s about a woman trying to live with what she has, not what she wants. I think that will always be a universal theme as long as humans continue to make choices of compromise. Because of circumstances beyond her control, Jean tries to make the best of it with classic midwestern stoicism. God, I know so many people like that today.

I agree! In fact, one of your greatest strengths in this novel is exploring the imagery of rural life in a relatable way that interpolates a variety of modern readers. How did the richness of a rural setting, especially the small agricultural community of the novel, influence the literary style of your writing?

I think living in a rural setting with limited choices or means of entertainment brings the surroundings into hyperfocus. It’s easier to notice small details—the sounds of nature, the rhythms of a household, the intimate interactions between people—with little noise or distraction, and so I worked hard to try and capture that hyperfocus in a way that felt relevant to the story and natural for my main character. And Jean is also an outsider looking in, doomed to only observe her heart’s greatest desire, so she’s constantly tuned in to the finest details.

Throughout the novel, Jean engages in various unnerving methods of self-harm. I have never read a book that renders these acts so uncompromisingly. Can you tell us more about the writing and editorial processes for these scenes?

I didn’t write the self-harming part of Jean’s character until a much later draft, and I think it evolved after working in the mind of this deeply repressed and unhappy character for so long. I felt like both she and I needed an outlet or expression for this inner pain and self-hatred she kept so tightly bottled up. The first time I showed a draft with the new self-harming scenes to a reader, it was to my then-agent, and I don’t remember worrying about what my agent’s reaction was going to be. She thought the scenes worked and strengthened the character, and we didn’t discuss it any further.

Fast forward five years to when the book sold to MG Press in a much different climate of trigger warnings and a larger discussion of the effects of literature, and it was a very different conversation. I broached the subject with the managing editors, Pfaller and Russell, and definitely felt nervous about their possible reactions this time. But in the end, the three of us agreed that despite the dark, difficult subject matter, it’s an integral part of Jean’s story. I think because Pfaller and Russell are both writers themselves, they understood and respected the importance of an author’s vision and were totally supportive.

Regardless, the scenes weren’t easy to write, both artistically or personally, but they were true to the character and true to my own experiences, so ultimately, I wasn’t going to compromise.

The unwillingness to compromise is certainly a bold risk that makes your work stand out and offers realistic insight about an often undiscussed suffering. Another theme that stands out to me is a multidimensional feminism. As wives and mothers in the 1960s, Jean and her sister-in-law, Liz, hold womanly authority in vastly different ways: Jean is respected for her skills in sewing, cooking, and farming, while Liz is young and sensuous—enjoying sex, taking birth control, and reading The Feminine Mystique. Aware of these distinctions, Jean speculates that Liz will eventually have to join the tradition of requesting the grocery money from her husband each week, just like everyone else. How do the time period and setting make The Good Divide a unique exploration of feminism?

One thing that really intrigued me about setting the book in the ’50s and ’60s is that it was a period of great change and transition for women, with some women embracing the changes quickly, like Liz, while others had a knee-jerk reaction to resist and doubt it, like Jean. And that was absolutely true in the conservative Midwest during that time. Many women didn’t appreciate the progressive efforts for equality and resisted change. So, for the story, there was a real opportunity to put two characters together on totally different ends of a spectrum and then watch them interact. I liked exploring the idea that Jean felt real worth and value in her domestic roles, and it wasn’t until Liz arrived and made it clear from the start that she wanted to live a very different kind of life that Jean started to feel self-conscious and become defensive. Even today, women are so guilty of criticizing or taking great offense to someone else simply making a lifestyle choice different than their own—to be a working parent or stay-at-home parent, to breastfeed or bottle-feed, and on and on—so I had plenty of firsthand experience to draw from.

The novel is bookended by Jean’s first-person narrations titled “Mistresses,” the second of which serves as a kind of epilogue. Without giving away any of the shocking plot twists, can you tell us more about the characterization of Jean? When you first conceived of the novel, did you know you would be including this section from Jean in her old age?

The bookend “Mistresses” chapters came from a theme of mirrors throughout Jean’s life that developed as I got deeper into the story. Once I spotted it, I really made use of it. I envisioned Jean as a woman somewhat doomed to repeat her mistakes, thus creating this mirror effect of her past and present—her tenuous relationship first with Sandy Weaver then later Tommy’s wife Liz, and then her involvement in pivotal moments of crisis for both Sandy and Liz. Also, physically the farmhouses are mirror images of each other, built and previously occupied by twin sisters with their own complicated history and relationship that’s hinted at. (I’ve actually sketched out another novel that is the story of Eunice and Beatrice I hope to write one day if I ever get around to it.) And finally, I finished off Jean’s mirrored narrative with the “Mistresses” bookend chapters.

The opening “Mistresses” were the first pages of the book I wrote, and I knew all along I would close the book with an epilogue-like version of that opening. What would come in between, though, I wasn’t exactly sure.

That mirroring serves as a complex theme throughout the novel, and it really works. You have an MFA in creative writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and have taught writing and literature at Drake University and Lindenwood University’s MFA program. What is one piece of advice you offer your students that you struggle to implement in your own writing?

Plotplotplot! It’s my Achilles heel. My writer’s instinct is to write from a character first and let a plot evolve naturally around that character, but I often end up with “quiet” plots that lack a great hook, lack narrative tension. Most books sell to publishers on big plot ideas and concepts, and yes, engaging characters, too, but really, it’s the plot that gets pitched first and piques interest.

I see beautiful writing all the time from students—funny dialogue, rich and interesting characters—but I also commonly see the same ailment I fight—soft plots or too little conflict. Or the opposite—a dense, convoluted plot. And in my experience, stories live or die by the strength of their plots, despite exquisite sentences or fascinating characters.

And unfortunately, plot often gets overlooked even though it’s the brick and mortar of the entire story. It holds everything else in place. Your characters, dialogue, setting, and details, all feel like they have a purpose, a raison d’être, because of the plot. I try to teach plot with this straightforward, reason for being, kind of approach to help students (and myself) build a novel that will keep the reader turning the page. Because at the core of this, that’s all we want. For the reader to keep turning the page.

Excerpt

August, 1963

Mornings, before the children awoke, Jean scrubbed her kitchen floor. She rose as soon as the alarm went off at 4:30 on her side of the bed and shook Jim’s arm until he blearily sat up in his night shirt and jockey shorts, and while he dressed for the morning milking, she went downstairs, started the coffee, and scrubbed her floor.

On her hands and knees, with the mixed aroma of dark roasted beans and lemon-scented soap, the rhythmic shush shush shush of stiff bristles across the linoleum lulled her into feeling like she was somehow wiping the slate clean from the previous day.

Once the floor was clean and the coffee brewed, she made an egg-and-toast sandwich that she took to Jim in the barn, along with a steaming mug of coffee. He ate the sandwich in less than five bites while seated on his squat wooden milking stool, and drank the coffee in less than five gulps, somehow never scalding his mouth. If it was Tommy’s week to work the morning shift, the coffee and egg sandwich were delivered to him. The morning routine was as reflective and dependable to her as breathing, and Jean was never a woman to appreciate change or surprise.