“Books are not published in a vacuum,” wrote researcher and professor Philip Altbach in 1975. His article, “Publishing and the Intellectual System,” discussed a variety of social, political, and economic trends that directly and indirectly affect the publishing industry. But trends in current political events speak to Altbach’s statement as though the quote were tailored to them.

In recent months, it has become difficult to point to a sector of American society that isn’t touched by political turmoil. Our recent presidential election and the mirroring Brexit vote across the pond mark deep and shifting partisan divides that show themselves in business, sports, educational communities, and the arts. Rather than being distinct from these communities and their conflicts, the publishing industry—because of its very nature—must both contain them and be contained by them.

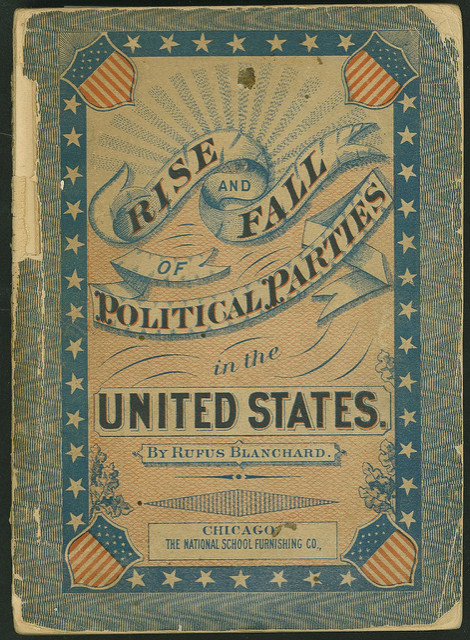

Of course, the relationship of politics to publishing is nothing new, especially in the United States. Don’t believe me? Google Benjamin Franklin. However, our present epoch of the celebrity memoir lends itself beautifully to political crossover. In modern times—where everyone is not Benjamin Franklin—almanacs have gone out of style, fame sells books, and politicians and pundits can advance their personal brands and agendas while providing the publishing industry with highly marketable and successful books.

And those brands and agendas run the spectrum of partisan politics. Consider Barack Obama’s Dreams of My Father, Bill O’Reilly’s A Bold Fresh Piece of Humanity, or Elizabeth Warren’s A Fighting Chance. Then remind yourself that these books stretch far beyond memoir into genre fiction (e.g., Glenn Beck’s political thrillers), and even children’s books (e.g., Rush Limbaugh’s time-traveling history lesson).

These precedents have done little, however, to soften the recent backlash faced by publisher Simon & Schuster after their Threshold Editions imprint offered a six-figure book deal to Milo Yiannopoulos, Breitbart editor and banished Twitter troll. Authors and media condemned the publisher for amplifying hate speech and offering substantial compensation to a man who is essentially famous for saying mean things about people on the internet. But in a sea of liberal and moderate publishers, conservative-leaning imprints command their own market, and Yiannopoulos’s book deal may indicate the emergence of a new audience shaped by decades of its own underdog narrative. This audience is alt-right adjacent and highly controversial, and it recently celebrated a presidential victory.

The Yiannopoulos book, reported to be an autobiography titled Dangerous, was eventually pulled by Simon & Schuster in the wake of controversial comments from Yiannopoulos regarding sexual relationships between young boys and older men. However, it remains an example of the ways that books become ammunition in sociopolitical struggles. In the progressive-leaning fields of education, arts, and literature, it is difficult to reconcile the market for such a book with a progressive moral imperative. It is important to remember, though, that books bleed both ways. Even as the arguments fly back and forth about whether the political movement that raised Milo Yiannopoulos to fame created a cultural imperative to spread its word, we also use the cultural collateral of books to laud a progressive political mind. In the days before the 2017 inauguration, a New York Times article presented a nostalgic retrospective examining President Obama’s literary tastes—books he read and appreciated during the last eight years. It’s written with clear partiality, comparing Obama to Lincoln multiple times, but it also reads as liberal literature for dummies, referring to the writings of Martin Luther King Jr., Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela, as well as books by Colson Whitehead, Zadie Smith, and Junot Díaz.

Whether arguing the merits of Dangerous or celebrating Obama’s literary mind, we are placing books and the publishing industry at the center of an old debate that calls for free speech versus hate speech, that pits conservatives against liberals, and that values classics over best sellers. But the thing about the publishing industry is this: books and politics have both been around for a long time, and as long as we have them both, they’re going to interact. To crudely paraphrase Gandhi, we are tasked, then, with creating the content we wish to see in the world. If we don’t, we’ll be denying Philip Altbach’s truth, attempting to publish books in a vacuum.