In a previous blog post, we discussed how editors in the comic book industry have their work cut out for them. While they’re certainly not the only type of editor who deals with multimedia editing, comics and graphic novel editors face unique challenges compared to those who deal with more traditional texts like children’s books or even textbooks. One of the key differences in this type of editing is that graphic novels utilize sequential art to tell the story, as Scott McCloud states in Understanding Comics. While other editors still have to look at whatever images they’re using, comics editors need to pay equal or even greater attention to the art.

A few years ago, I had the great opportunity to write and edit a two-page comic with artist Tim Sale for a class. In truth, my script was lackluster (though it had enough emotion for a two-pager), and I was told this is far from uncommon. Portland-based comics educators Big Red Hair state there are two different kinds of scripts: a “plot first” script, and a “full script” that is more reminiscent of Alan Moore’s infamously detailed scripts. When using a “plot first” script, much of the storytelling is actually up to the artist. Naturally, the editing process begins with the script. While my own two-page plot-driven comic was hard to edit, something with more length and depth often needs even more editing. To get started, the author might ask questions commonly posed at the developmental editing stage, for example, “Does it make sense that we’re going from A to B with this character development?” A lot of that may still need to be tweaked once the artist has begun their work, but the more editing that can be done beforehand, the better.

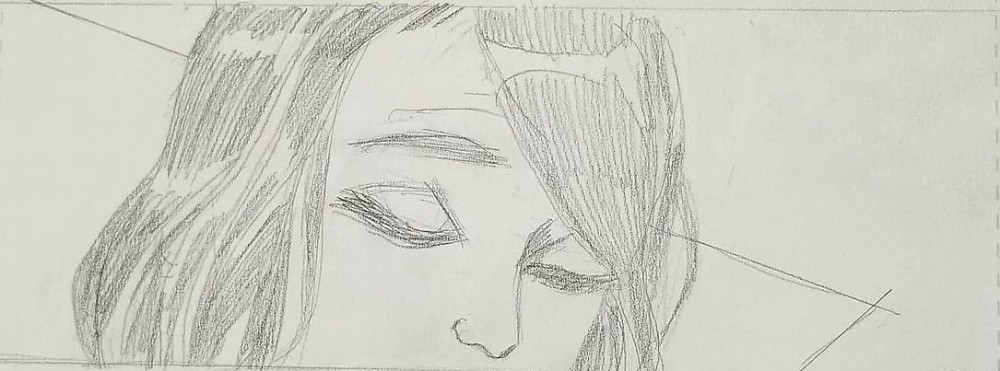

One of the biggest tools for a comic book editor is something called “the prelims,” or the preliminary sketches. These rough sketches detail how the artist is going to lay the pages out.

Preliminaries for Denouement by Anastacia Ferry and Tim Sale

Admittedly, a prelim such as this doesn’t look like much from a storytelling perspective. However, these scribbles allow the editor to get an idea of the page layout. One of the first things an editor might ask is whether the gutters (the spaces between the panels) are too distracting. While this may seem like a trivial thing to look at, Scott McCloud explains that gutters help a reader fill in the blanks between panels and are one of the tools used to help convey the passing of time.

Next, an editor might look at the inside of the panels. Does the clutter on the left distract from the main characters? Is the clutter necessary for the story? Like with traditional literature, too much unnecessary description can take the reader out of the scene. In this example, if the clutter detracts from the girl crying, we’ve completely changed the tone of the story. Similarly, if text is going to be represented on the page in word bubbles, will there be enough space for the bubbles without taking away from the scene?

The editor can also look at it from a developmental editing standpoint. Something that may not have been as clear in the script or purposefully left up to the artist’s interpretation may seem a little strange now that they have the preliminaries. If a superhero is jumping from building to building, are the heights or locations of the buildings remaining consistent? Does a character suddenly have more than two hands?

While an editor within the comic book industry is far from done at this point, this illustrates some of the challenges of editing comics. A large amount of the storytelling within comics and graphic novels has to do with the artist, and that’s a relationship that many editors in the publishing world will never have to deal with. From here, a comic book editor will soon have to work with the inker, colorist, and letterer to ensure the story is told the way it was envisioned.