You step into a Japanese bookstore. Wall to wall you see nondescript, two-tone spines with black lettering, so you decide to search by author and genre. Unfortunately the books are grouped by publisher and you don’t know which one you are looking for, so you ask the attendant for help. He tells you, “That’s a foreign book. We only stock bunko, or proven bestsellers.” And it’s the biggest bookstore in town.

Much like in the West, the Japanese publishing industry was hit hard by the rise of digital media and the Barnes & Noble–style superstore. These changes and the resulting panic they caused have largely settled down in the West, where print has proven to be resilient to total destruction, but publishers are struggling to remain relevant by adopting new technologies and upending traditional business practices. Can the same be said for the nation that, in 2016, does business almost exclusively through fax machines? No, seriously . . .

Yes, Japan’s book publishing industry is almost certainly in the toilet, and there’s plenty of blame to go around. With Apple, Google, and Amazon slowly but surely expanding their digital distribution services in the country, the problems will only compound. But I’m more concerned with what we can learn from this as future publishers in a risky business. How did it go so wrong? Here is just a taste of what I think happened:

- Japanese Pricing Models and Return Rates Are Insane – The Japanese bookseller is operating on saihansei, or consignment, meaning they don’t have to pay for their stock and instead are making 20 percent on each product sold to the consumer. If the book doesn’t sell, it can be returned to the publisher, just like in the West. There is, unfortunately, a huge caveat to this system: the vast majority of Japanese books are priced by the publisher, and the price cannot be adjusted at any point in distribution or sales. This hurts the publishers the most, as a poorly judged market can mean unprecedented rates of return, sometimes averaging over 50 percent. While there have been pushes to deregulate this rigorous sales model, Japanese publishers are resistant to losing total control over their products in the storefront.

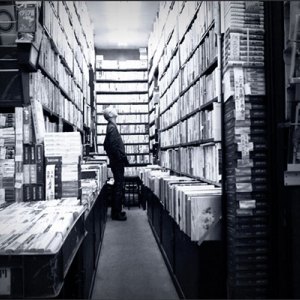

- Foreign Titles Are Almost Universally Disregarded – Earlier, I mentioned Bunko, or mass-market bestsellers. They are small, paperback books with undecorated spines and little to no cover art. They are also virtually the only format for foreign works in the Japanese bookstore. Scouts for Japanese publishing houses will typically only choose certified bestsellers with clear mass-market appeal for localization, and they don’t choose many of them. It is estimated that only 8 percent of the books on sale in Japan were originally printed in other countries, and that 8 percent doesn’t mean the newest and hottest books on the international market. It’s not uncommon to see nearly all foreign shelf space taken up by ancient but proven backlisted titles. Patricia Cornwell, Michael Connelly, and even Aldous Huxley—deceased since 1963—take up the most visible and marketable positions in Japanese bookstores. Here is a great article on the impossible challenge for the foreign bestseller in Japan if you’d like to delve a little deeper.

- Print Media is Not Made Valuable in Japan – Many western publishers put a remarkable amount of effort into increasing the heft, build quality, and aesthetic appeal of the books they release. Why do so when condensed paperbacks are so much cheaper to produce? Because a consumer will perceive a bigger, prettier book as more valuable, though not strictly from a monetary perspective. A book’s build quality and art are powerful marketing tools, as a fancy book becomes more than just its contained information. It can also be sold at a greater profit margin. In Japan, however, there are almost no hardcover books, especially in trade publishing. Even guaranteed bestsellers are printed in a publishing house’s uniform paperback style, devoid of the typical artistic embellishments of the western hardcover. And if the value of a text is solely the information within, then what’s the incentive for purchasing physical over digital?

Ultimately, these examples show that it was an unwillingness to change that brought Japanese publishing to its knees; a steadfast reliance on older models of sales and consumption that couldn’t hold up in a more competitive market. Now, Japan seems to have no choice but to prepare for the all-digital future that we are actively and consciously adapting to in the West.