When I was ten years old, adults in my life made a big deal about public schools no longer teaching cursive. “How are you going to pass your SATs without cursive?!” they’d cry, while I would cry over sheets of dotted lines and swirly words. While they were right about needing it for the SATs, I have since retained only enough cursive to spell my name for legal documents. Like many other millennials, I felt my time was wasted learning an archaic skill instead of something more contemporary and more applicable to day-to-day life. It would be another two years before I learned typing, a skill I employ daily at Ooligan.

People my age have been fed the “old way” with the expectation that we’ll need to write everything by hand, that we won’t have a calculator in our pockets every day (in the form of phone apps), and that we’ll need to memorize every phone number and address we ever encounter. Is it really that surprising that our generation is cynical about any analogue workflows when we’ve seen several outmoded in our lifetimes? Unfortunately, it is that exact disillusionment that causes some genuinely useful pre-Y2K skills to be overlooked. Case in point: hand-marked editing.

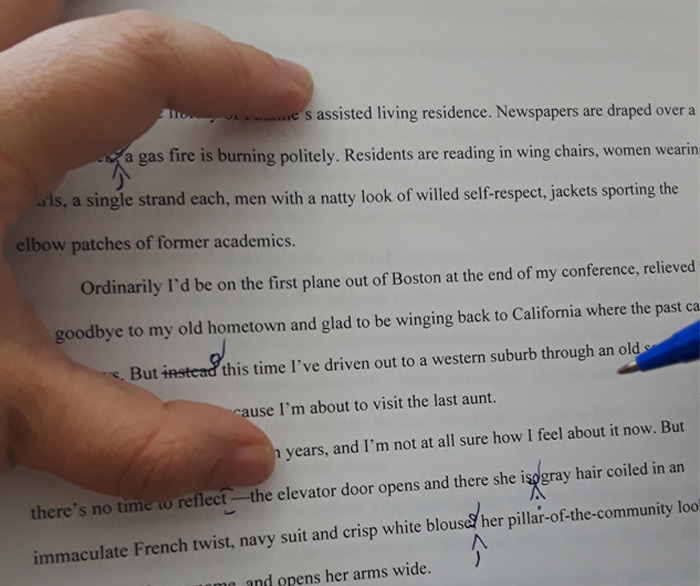

Undeniably, digital copyediting has its benefits: more room to comment, capacity to share work instantaneously, automatic spell-check. But you lose things, particularly the readability that comes with line editing in the margins of a printed copy. Jason Fried succinctly described this digital fog in his article “Copyediting: Man vs. Machine”:

For example, to suggest a capitalized “A,” you’d triple-underline the letter by hand. But on a computer you’d actually replace the lowercase “a” with an uppercase “A,” but the remnant “a” would remain. Over the course of many sentences and many changes, the machine-made track changes edits blend in too much with the original text. It becomes hard to quickly spot changes. And it becomes hard to actually read the original to the changes.

This added readability is helpful not only for the author receiving the edited manuscript back, but also for the editor’s chances of catching mistakes in the first place. How often is it that you print out an important term paper thinking it’s totally fine while it’s on the word processor of your choice, only to find you used the wrong version of “there” or typed “form” instead of “from” in a crucial sentence? If you were paying someone to catch those sorts of mistakes, you would not be happy if they missed them for the exact same reason you did.

Finally, there’s the simple fact that certain writers (and, indeed, entire presses) are, and will continue to be, Luddites. Whether they were raised in the age of typewriters and never had time to learn other ways or are rightly skeptical of the privacy afforded to modern word processors, changing their minds on the matter isn’t easy, and attempting to do so can be unprofessional. In those cases, editing by hand is really the only option, even if the idea of the author painstakingly inputting your edits and essentially writing the manuscript twice makes you cringe. Our place as good editors is to be rigid about grammar, not the form in which we deliver our edits.