Even though social media theoretically closes the distance between an author and their readers, it sometimes seems to me that the opposite is true. Just looking at a particularly famous author’s feed, I’m highly aware of the statistical improbability of actually getting their attention on Twitter. As of early October, J. K. Rowling had 8.44 million followers, an absurd amount of people to compete with for her attention. John Green had 5.19 million, which is better, but still virtually impossible.

Though I generally consider such endeavors fruitless, I have fleeting moments of hope (or the inability to resist tweeting something insanely clever) in which I reply to an author’s tweet.

On June 16, John Green tweeted a picture of his recently reorganized bookshelf. I noticed a familiar-looking purple spine on the shelves and couldn’t help but ask whether he’d recommend John Updike’s Rabbit novels, noting that I’d heard mixed things.

Almost immediately, he replied.

After freaking out for a little while and drinking some tea to calm down, I went out and bought Rabbit, Run at Powell’s.

A few other authors have previously noticed things I tweeted, including Nicola Yoon, my favorite YA author Sarah J. Maas, and Joyce Carol Oates. Yeah, that Joyce Carol Oates. Actually, she’s retweeted me twice and liked several other tweets. (Of course, this has a lot to do with the fact that she spends an absurd amount of time on Twitter. It’s kind of concerning.)

That interaction with Joyce Carol Oates made me realize that although I’d read some of her short stories, I didn’t actually own any of her books. I went to Powell’s that evening and bought two: Foxfire: Confessions of a Girl Gang and Bellefleur.

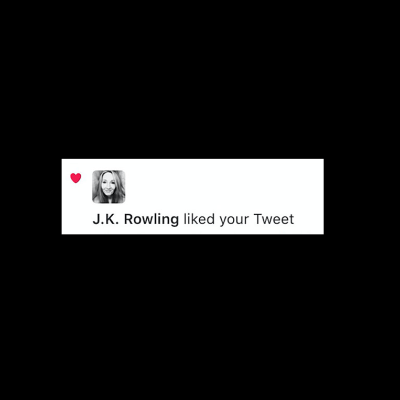

June 29, 2016, marked one of my crowning achievements in life: J. K. Rowling liked my tweet defending my Hogwarts house to some muggle who picked a fight with the wrong Hufflepuff. I’m just one out of 8.44 million Twitter followers, so the odds were not, as they say, in my favor. But she did notice me, and I had to check my phone multiple times throughout the day to make sure it was real.

I was embarrassed at how excited I was. I tried to convince myself it wasn’t a big deal. It was hardly significant to J. K. Rowling, so it shouldn’t mean so much to me. I never quite convinced myself of that, and I’m still kind of considering printing a screenshot of the tweet on a mug.

The value of these interactions, even for famous authors, is clear. Authors and readers have developed a community on Twitter and other social media platforms. No, J. K. Rowling is not particularly likely to interact with any given person, but the community she has set up around her makes such interactions possible.

The possibility of engagement is what unites the book community on Twitter. It’s the reason I know that Leigh Bardugo and Sarah J. Maas are friends: I see them interact on Twitter all the time. I love Sarah J. Maas, and once I knew she was friends with Leigh Bardugo, I bought Six of Crows as well. Visible connections on Twitter manifest themselves in real, significant ways, though they may not always be as quantifiable as my purchases.

Admittedly, I’m probably easier to convince to buy a book than most other people, but I think the logic holds true. Authors cannot engage with all their readers, especially when they have millions of followers. But that possibility of a connection with any one of those followers is what makes it so remarkable.

I mean, I bought the Updike books simply because John Green gave a mixed review about it, but he did so directly to me. The Rabbit books are now on the radar of others who saw those tweets, and I’m willing to bet that at least one of those people has bought them. The retweet from Joyce Carol Oates was like she was accepting me into her little community of readers, after which I felt like I had an obligation, as part of this group, to buy her books.

Part of me still feels a little silly for caring so much about these simple little Twitter interactions. But to butcher and repurpose a Dumbledore quote: “Of course it is happening on Twitter, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”