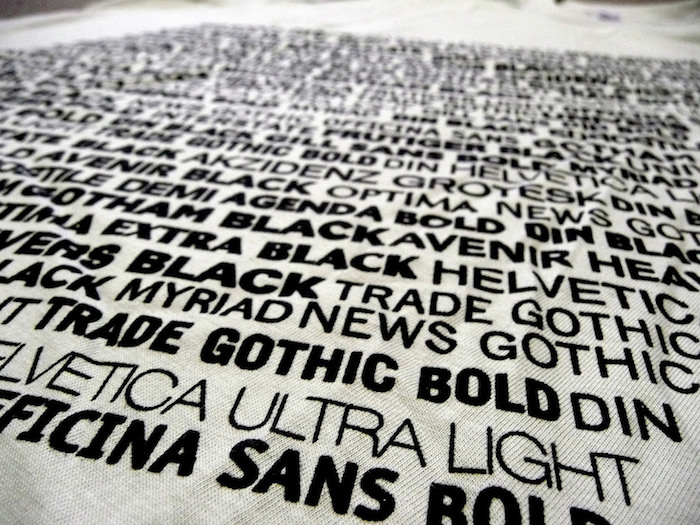

The Psychology Behind Serif and Sans-Serif Fonts

There are a lot of arguments out there that try to establish that one typeface is inherently better than the other. Traditionalists value the more conservative, classic sense of structure and reliability that the serif font brings to a design. On the other hand, those who favor a more modern aesthetic use sans-serif fonts to convey a sense of friendliness and informality.